Transformer Architecture

Tokenizers

What it does: encode string(like utf-8 encoded text) into a list of integers(token ids).

Why we need it: if we use utf-8 as the vocabulary directly, it would be too large and sparse.

- Too BIG: 154,998 characters.

- Too SPARSE: some characters don’t appear so often.

Purpose: create a way of encoding to make the vocabulary efficient.

Different types of tokenizers:

- Word-level tokenizer: map each word to token ids.

- Too much words.

out-of-vocabularyissue: there are always new words.

- Byte-level tokenizer: directly use raw bytes as token.

- Solves

out-of-vocabularyissue. - Scale Issues: Results in extremely LONG input sequence, which: slows down model training, creates long-term dependencies in data.

- Solves

- Subword-level tokenizer: a trade-off between the above.

- larger vocabulary size(the number of possible tokens) <==> better compression of the input byte sequence.

Key Concepts:

- Vocabulary size: the number of possible tokens

- Compression ratio: how many bytes does a single token represents in average

Byte-Pair Encoding(GPT-2)

- Pre-tokenizer: divide a sentence into parts.

- 中文如何pre-tokenize?

- Special tokens: like

<|endoftext|>should always be treated as a whole. Determines when to stop generating, etc.

Parameter Initialization

For a linear model like \(y = Wx\), we need to keep y from blow up(overflow) when input dimension grows.

Simply, we initialize parameters like \(\frac{W}{\sqrt{input\_dims}}\), use a gaussian distribution to initialize, and truncate for extra safety.

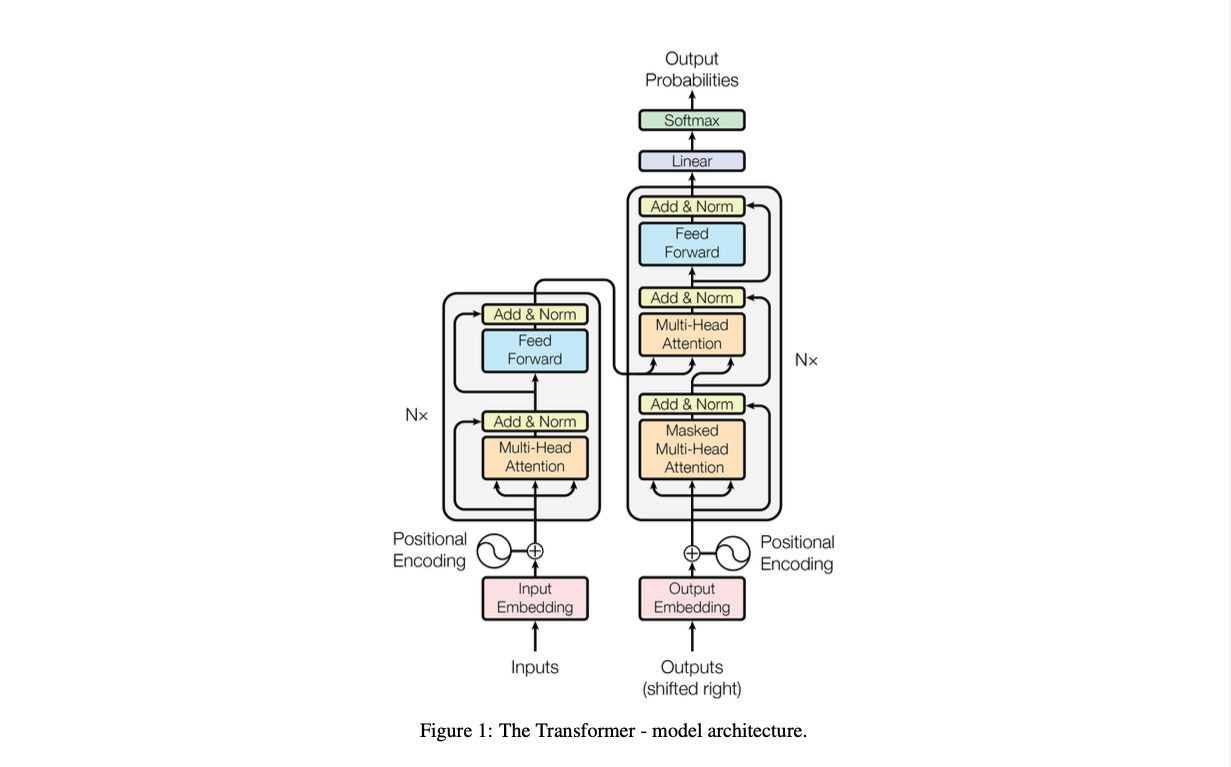

All(1/3) you need is attention.

Post-Norm vs Pre-Norm

Activation functions

Positional Embedding

Hyper-Parameters

Feedforward layer, two dimensions: the feedforward dim(\(d_{ff}\)) and model dim(\(d_{model}\)), their relationship:

\[d_{ff} = 4 \ d_{model}\]Almost always true.

Exception #1 - GLU variant: scale down by 2/3. So most GLU variants have \(d_{ff} = 8/3 \ d_{model}\). Exception #2 - T5 - 64 multipliers.

Takeaway: for \(d_{ff} / d_{model}\) ratio, there are conventions, but the choice isn’t written in stone.

Multi-head vs. Single-head self-attention.

If the ratio is 1, it’s computationally efficient compared to single-head.

\[\frac{d_{head} \times N_{heads}}{d_{model}} \approx 1\]Aspect ratio, how deep should my model be?

\[\frac{d_{model}}{n_{layer}}\]GPT2 is 33, GPT3/QWen is 128, LLaMA/LLaMA2 is 102.

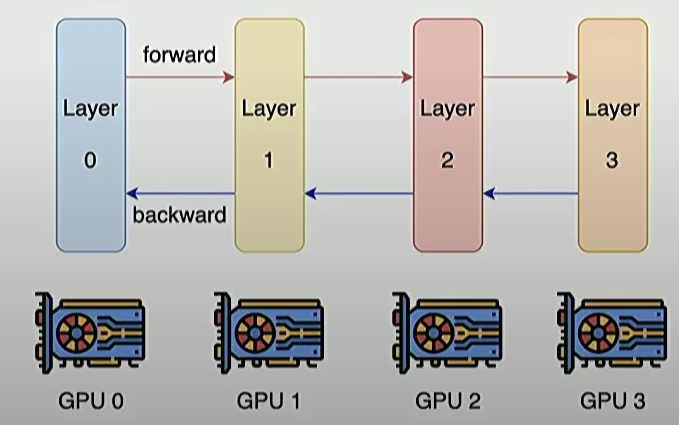

Extremely deep models are harder to parallelize and have higher latency.

Distribute computation for each layer to different GPUs -> wait for previous layer. This unlike width, which can be easily parallelized over thousands of devices.

Sweet spot of aspect ratio is around 100 [Kaplan et el 2020].

Vocabulary size?

Monolingual models ~ 30-50k. Original transformer - 37,000, GPT2/3 - 50257, LLaMA - 32,000.

Multilingual / Production systems ~ 100 - 250k. GPT4 - 255,000. Deepseek - 100,000. Qwen 15B - 152,064.

Regularization

Do we need regularization during pre-training like dropout and weigh decay(e.g. AdamW)?

Argument against - not likely to overfit:

- Too much data » parameters.

- SGD only does a single pass on a corpus(hard to memorize).

In practice, many older models used dropout during pre-training. Newer models (except Qwen) rely only on weight decay.

Why weight decay LLMs [Andriushchenko et al 2023]?

- It’s not to control overfitting(has no effect), because no improvement over validation loss.

- But there are some improvement over training loss. Weight decay interacts with learning rates(cosine schedule). There are some complex interactions between optimizer and weight decay to cause this effect.

Takeaways: we still “regularize” LMs but its effects are primarily on optimization dynamics.

Stability

Problem child - softmax not very numerically stable.

- exponential.

- divide by zero.

Solution 1: Z-Loss(for output layer). Solution 2: QK-Norm. Solution 3: Logit soft-capping -> might have performance issues.

Attention heads

1:15:12